There’s a news report circulating that China announced it had linked its digital RMB cross border payment system to ten ASEAN countries and six Middle Eastern jurisdictions. We have not been able to trace this to a reliable source, so it may be fake news. However, the substance of the report is not a million miles from the facts. It’s likely jumping the gun by a few years.

China is a member of mBridge, a cross border payments joint venture using central bank digital currency (CBDC). The Chinese end of any payments uses its digital RMB CBDC, but mBridge does not belong to China. Other member countries include Hong Kong, Thailand, the UAE and Saudi Arabia. As of late last year there were a couple of dozen observers. If one counts the observers (which is a big leap) then it would have covered five ASEAN countries and six Middle Eastern ones.

Why mBridge is not a threat. Yet.

The first English language report about the ASEAN/Middle East footprint came from a Nigerian outlet Proshare. It noted that the news implies “that about 38% of global trade could bypass the US dollar dominated SWIFT network.”

In order for it to reach 38%, not only would all the central banks in each of these countries have to be connected to mBridge, but so would all their commercial banks. Judging by the slow and gradual adoption of mBridge by Chinese banks, today that 38% is extremely theoretical. That’s not to say it couldn’t be a substantial figure in a few years.

Additionally, in order to reach 38%, all the countries would have to shift 100% of cross border payments to local currencies. Today a large proportion of trade is denominated in dollars.

There’s a good reason for that.

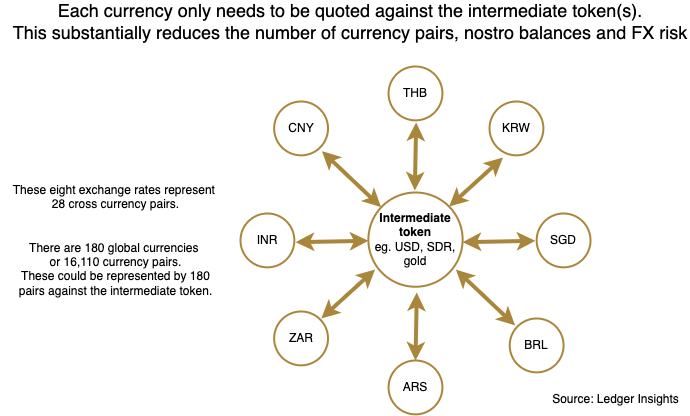

For virtually every country in the world, their optimal foreign exchange rate with the narrowest margin is against the dollar. That’s because having a single intermediate currency means there are a lot more buyers and sellers for that exchange rate. By contrast, if you look at every cross currency exchange rate, for 180 global currencies there are 16,110 cross currency rates, most of which are thinly traded, making them expensive.

If a trader chooses to invoice in their local currency or the currency of their customer, one or both of them will have to suffer the cost of a suboptimal exchange rate.

So even if the government thinks local currency is desirable, the cost of choosing the trading currency falls on merchants, who usually want to save money, so they choose dollars.